Grounding is something that every signal Soldier should be familiar with. I would hazard to say that, we have all heard of it, all acknowledge the fact that it is an import step during the setup of any signal system (it is hard to find a technical manual for a piece of equipment with a power plug that doesn’t mention grounding at least once) but few people understand why we need to do it and even fewer know how to do it properly. The grounding of signal equipment serves two important purposes. First, it is a vital safety step that must be taken to minimize the risk of electrical shock. Secondly, proper grounding helps ensure that the equipment (especially transmission equipment) outputs its signal properly to allow for dependable operation.

Grounding helps protect personnel and equipment from faulty power supplies and from lightning strikes. In both of these cases, a sudden unexpected surge in electricity can severely damage equipment or possibly cause injury to nearby personnel. A properly grounded system provides a low resistance path for that electricity to discharge itself into the earth where the effects are harmless.

Signal equipment, especially transmission systems depend on a clean signal to ensure that data is transmitted without distortion or error. A good ground on these systems can often reduce the noise found on transmission circuits, ensure proper timing across serial links and reduce interface errors or Ethernet interfaces.

While it is not my intent to teach you how to properly ground a system (please follow the instructions supplied in the appropriate technical manuals), I want to point out some important things to consider when it is time to ground your equipment.

Grounding Systems

There are a variety of different ground systems available for use today. Each one has its pluses and minuses but they all ultimately have the same goal of providing a low resistance electrical path to the earth. Three different styles of ground systems are commonly found with signal equipment.

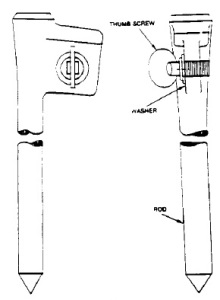

The simplest grounding system is the solid ground rod. They can be normally be found in six and eight foot lengths and were normally associated with signal shelters. The design is simple, just a single solid metal rod with a driving head on the top of it and a thumbscrew coupling on the driving head for the ground strap. When I was a young private I learned the important lesson of first removing the thumb screw while you were driving the ground rod into the dirt (or you were very likely going to sheer it off) and to tape two tent stakes around the head of your sledge hammer to protect the handle from being damaged due to repeated misses (these things can get a pretty good shake going when you first start to drive them in).

The simplest grounding system is the solid ground rod. They can be normally be found in six and eight foot lengths and were normally associated with signal shelters. The design is simple, just a single solid metal rod with a driving head on the top of it and a thumbscrew coupling on the driving head for the ground strap. When I was a young private I learned the important lesson of first removing the thumb screw while you were driving the ground rod into the dirt (or you were very likely going to sheer it off) and to tape two tent stakes around the head of your sledge hammer to protect the handle from being damaged due to repeated misses (these things can get a pretty good shake going when you first start to drive them in).

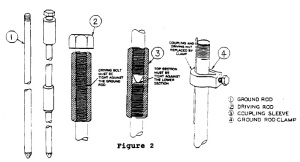

The next kind of ground rod is the multi section ground rod. In my experience, these are often found with generator sets. It consists of multiple sections of ground rod that are able to be coupled together to create a rod of various lengths with the ultimate goal of getting a rod long enough to hit moist soil. For these it is important to use the supplied slide hammer and strike plate instead of a normal sledge hammer or it is likely you will strip the threads of the coupler and be unable to remove it.

The next kind of ground rod is the multi section ground rod. In my experience, these are often found with generator sets. It consists of multiple sections of ground rod that are able to be coupled together to create a rod of various lengths with the ultimate goal of getting a rod long enough to hit moist soil. For these it is important to use the supplied slide hammer and strike plate instead of a normal sledge hammer or it is likely you will strip the threads of the coupler and be unable to remove it.

The final system that I see more and more often is the so-called “star” ground which consists of 15 relatively short stakes connected together by a long length of aircraft cable. The idea being that the combined ground potential of the numerous rod into the ground with the surface area of the cable provides an electrical path similar to what you find with a traditional ground rod. In my experience, these systems are significantly easier to setup (not having to go nearly as deep into the dirt) but are also the most likely to be setup incorrectly. When using the star ground it is important to remember that the entire length of cable must be used in order for it to work properly and that tension must be kept across the entire cable to provide the best grounding path. This is normally done by giving each stake a slight turn prior to putting it into the ground.

The final system that I see more and more often is the so-called “star” ground which consists of 15 relatively short stakes connected together by a long length of aircraft cable. The idea being that the combined ground potential of the numerous rod into the ground with the surface area of the cable provides an electrical path similar to what you find with a traditional ground rod. In my experience, these systems are significantly easier to setup (not having to go nearly as deep into the dirt) but are also the most likely to be setup incorrectly. When using the star ground it is important to remember that the entire length of cable must be used in order for it to work properly and that tension must be kept across the entire cable to provide the best grounding path. This is normally done by giving each stake a slight turn prior to putting it into the ground.

Other Considerations

A few other things to remember. First, the ground strap connecting the ground rod to the system has to be tightly secured to it. This means using some sort of camp or nut to connect the two. I can’t count the number of times that I see the ground strap looped around or “tied” to the ground rod. It doesn’t work. Next the type of soil you are going into matters. Dense wet soil is great. Sand and gravel (like what you see here at NTC) is horrible. Unfortunately, you normally can’t pick the type of soil you’ll be putting your ground rod into so if you have horrible soil, make it less horrible by adding water and rock salt to improve its conductivity. This is something you have to do regularly (not just once when you first arrive on site).

Pointless Stories

Just to illustrate my points I’ve got three personal experience stories that help illustrate my point on grounding.

- Out in the field in Korea 2000 setup at a node center site. One of our KATUSAs is on the DNVT in the LOS shelter while everyone else is under our ponchos staying out of the rain during a storm. Lightning strikes the hillside and grounds into the node center. The charge travels down the WF16 and shocks the hell out of CPL Lee who happened to be on the phone. He comes running down the hill screaming, stops in front of us, and passes out and had to be medevaced off the hill. He was fine.

- Also in Korea 2000 doing a switch exercise in the motorpool. The node center has cable shots connecting a RAU and several SEN shelters to it. Lightning hits the RAU antenna and travels into the com modem where it travels down the CX-11230 into the node center and branches off to a couple of the SENs frying nearly $500k in CCAs between all of the shelters, all because the systems weren’t properly grounded.

- Iraq 2008 one of my teams is installing a HCLOS link (sans shelter, just the radio and antenna) to a data package connecting it to the house power. Shot wouldn’t come in for days. Put a multimeter to the power source and find dirty power. Ground the system properly and the shot comes in. Who’da thunk?

I have included a few documents I found from CECOM that relate directly to grounding. They are older, but I am pretty confident that electricity hasn’t changed a lot.

- CECOM TR-96-2 Earth Grounding Pamphlet

- Tech Bulletin #9: Safe Grounding of Communications Equipment in the Field

- TM-11-5820-1118-12&P (Star Ground)

“Shot wouldn’t come in for days. Put a multimeter to the power source and find dirty power. Ground the system properly and the shot comes in. Who’da thunk?” LOL I would! 90% of the time systems don’t “work right” it’s bad power and/or ground…

I am stealing this.

Troy great artical… Before flying I was a 31C with a lot of HF experience. Like you I cannot tell you how many times over the last 10 years I have seen TOC’s, CP, COM Centers set up with improper grounding, and everyone wondering why LOS communications is bad. Cruddy generators, KBR contract electical labor, and the signal school really no longer teaching the lost art of tactical communications are all factors in degraded tactical signal. Seems like unless you go to JCSE or SOCEUR, JCU etc… You are not taught the tactical basics and more importantly the theory behind it. Well done, good artical.

The 35th SIG units I was in (D Co 327 and B Co 51) employed proper grounding methods at the locations I was stationed.

We used the 9-fter for the shelters with the head clamped/bolted in a 3×3 holes which we added water to every shift.

We used the multi-rod system with 3-3 ft sections and a slide hammer. Properly spaced and clamped/bolted together. Hole and water as well.

Then, for our second OIF dep, we got the star-ground set. It was deployed the same way as the pictogram in the article.

Another poignant note should be the other connection point. Double check that it is correctly connected and not tied/disconnected/loose/etc. Then, if you want to impress the brass, bust out a Multimeter and Ohm it out to 20.

After the Gulf War we kept our ground pits moist without wasting our prescious fresh water. But therre is a ‘nicer’ way too – run a garden hose from the ECU condensation drain to your ground pits – it’s just like drip irrigation. If there is too much, move it around from pit to pit.

Good stuff, thanks for the write up (really like the HUMVEE parked on top of the ground rod – made me laugh).

Unfortunately it made me just shake my head and take a picture. Eventually grabbed the Net Tech and took him for a walk around his line afterwards.

Chief you yet again hit another topic where it just hits home.

I just taught my company proper grounding (among many other old doctrine site setup examples) and it absolutely baffled me why these guys had no idea how to ground much less why we do it. I work in a DIV NetOps and we are hitting a new DIV Standard hard since there never was one.

The TTPs and Evaluations for the equipment is readily available but these young team leaders don’t even know what they are much less how to properly train with them to try and certify their teams.

I would love to help be part of a larger initiative to fix all of these things we see around the army.

Long gone are the days of team ex-evals or crew drills where those team leaders had to get the OPORD, conduct site surveys get the grid coordinates, ensure they get the right tech data, roll out, properly install the assemblages, all the while ensuring site security is being met.

Our nettechs are getting called for every little issue that should be able to be fixed by the team leader.

Then god forbid the STT starts having problems and the 25N team leaders says he can’t do anything until the 25S is at chow when the STT is literally on the Individual tasking for 25Qs.

I can’t seem to edit my post above but I was raised to do coppoer on copper metal to metal with the ground straps and I noticed the pic you said was good was a copper ground with metal strap. Is that to standard or were we just being overly redundant back in the day?

I am assuming you mean the photo up there with the ground strap “bolted” to the ground rod that is watered. To the best of my knowledge that is acceptable. The ground straps are what used to be and I think still are fielded with the JNNs and a lot of the other shelters out there.

Roger thats the one Chief. I have always used copper wire + polls + bolts for generators and the metal straps with the 6 footers. We never used the metal straps for the generator to connect to the copper ground rods.

Also 3 inches around, 2 inches deep with the top of the ground rod not protruding out of the ground (trip hazard).

It just seems like it is a lost art these days.

EDIT: Need to stop using my phone for these.

For clarification,

the 6 ft ground rods for the SEP and PEP w/ metal ground strap.

Now that you mention it, I honestly don’t know if that was connected to a generator or a shelter. Unfortunately when I went to look at the uncropped photo it didn’t show the other end.